By Angel Tobar

Aug 3 2023

The history of tobacco and the people who cultivated the plant have a deep, spiritual connection with it. However, this history is also complicated due to the exploitation of tobacco via the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Before colonialism, the plant was sacred to those who grew it. It had many medicinal uses and was also grown as a source of income by oppressed people under Colonial rule. For some, it was a way to connect with God; for most, it was the catalyst that led to the suffering of black and indigenous people for hundreds of years.

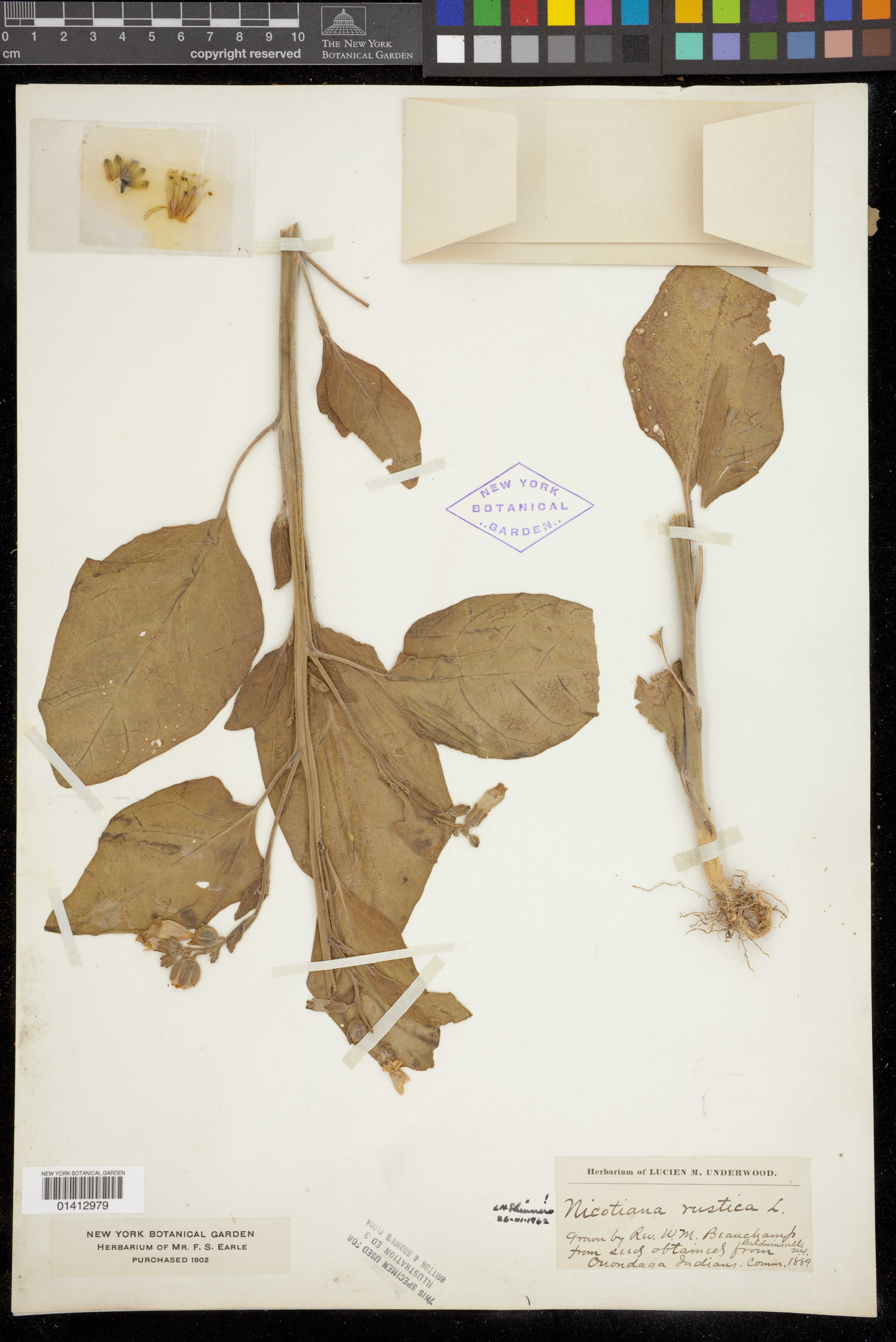

The Spanish and English words for tobacco are derived from the Arawakan Taino word “Tabako”, which means a roll of tobacco leaves (Kiple & Ornelas). The word "tabako" was also incorporated into the scientific Latin name for this plant: Nicotiana tobacum. The precolonial use and history of tobacco in the Americas vastly difers from postcolonial uses, perspectives, and connotations attached to the crop. It was considered sacred and used medicinally by many indigenous people but was quickly turned into a plantation crop by colonizers. Researchers think that Nicotiana tabacum was first encountered by Europeans in South America and the Caribbean. It was then cultivated and spread for botanical use by the Portuguese, Dutch, and Spaniards, so it inevitably made its way throughout Africa.

Tobacco is an herb that is now grown world-wide. It is a perennial that can grow anywhere from 2 to 5 feet tall, and its leaves are dried and prepared for smoking, chewing, and snuffing: “The leaves are alternate and carried on long petioles; they are entire, ovate to lanceolate, and are often longer near the base of the plant and reduced gradually in length toward the top. Most species sprout pale yellow, trumpet-shaped flowers, about an inch long, on terminal racemes or panicles. The flowers of N. tabacum are pink. All the flowers are five-lobed” (Salmón).

Tobacco was a used as a cash crop and was grown to help boost the economy of Europe, but it was a sacred plant that was used medicinally and for spiritual practice through many indigenous cultures. It was held in very high regard by indigenous communities, and in some instances, was the only crop that was grown by some hunter-gatherers. It is understood throughout these different cultures that tobacco must be used with respect, which is the opposite of its plantation use. Along with Nicotiana tobacum, the species N. rustica was also ritually used by various Indian tribes in North America. It is believed that our thoughts and prayers are carried into the spiritual realms through the smoke of tobacco (Salmón). This is aligned with the concept of 'Iwigara,' the Raramuri belief that all lifeforms are interconnected and share the same breath. “One of the meanings of Iwigara is ‘breath,’ and the general American Indian concept of breath is similar to that of soul, or sprit. Breath permeates all things and the universe. And humans share that breath. When we inhale the smoke of tobacco leaves, we are creating a unifying connection with all the cosmos. The smoke flows in and from our bodies, carrying with it our thoughts, further solidifying our connection to all things” (Salmón, p. 197).

Traditionally used by indigenous people as medicine, there were other things that tobacco could help with. It is medicine and a natural pesticide. It was used for understanding plant hybridization and to understand fundamental plant biology. Nicotiana tobacum was even the first artificially genetically modified plant species. It is now understood that tobacco contains many properties that, in moderation, can be beneficial to human health. The leaves are rich in pharmacologically active compounds, the well-known alkaloids nicotine and nornicotine, as well as other active compounds: guaiacol, quercetin, rutin, and eugenol. The effects of these chemicals give the plant the ability to act as a narcotic, analgesic, expectorant, and antispasmodic, along with animicrobial qualities (Salmón, p. 200).

There is a belief that Nicotiana tobacum was grown and used in Africa before the 17th century, but this a common misconception. Cultivated tobacco reached Africa through the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in the early 17th century. Over time, Africans developed their own individual relationships with the plant, regardless of it arriving there via the slave trade. In regions of Africa, such as modern-day Senegal, tobacco thrived very well. However, communities focused their efforts on harvesting plants and grains rather than cultivating tobacco (Laufer). While most of the Dutch and Portuguese smoked tobacco individually in their own pipes, Africans smoked from large pipes made from reeds that were more than 6 feet long; this way multiple people could smoke together (Laufer, p. 8).

The demand for tobacco was growing immensely at the end of the 16th century, and the Dutch, British and French traders were eager to buy (Baud). By the 17th century, tobacco was being cultivated all over the Caribbean, although many of the islands were still under Spanish control and exports by others were unauthorized. “In an economy where the circulation of money was very limited, easy-to-handle cash crops such as ginger or tobacco functioned as a mean for poor agrarian population to fulfill their religious and civic obligations and to acquire their basic necessities" (Baud).

As long people are under the control of colonial rule and influence, the people in power will do what it takes to silence those who seek to empower themselves. In 1604, the Spanish Crown evacuated the populations of northern Venezuela and Santo Domingo, which lead to despoblaciones. The governor at the time of 1605-1606, Antonio Osorio, ordered that the towns of these displaced people be burned down, which forced them to find new settlements in the central and eastern part of the country. This displacement of agrarian populations was an effort to keep people from growing their own tobacco to meet their own subsistence and economic needs, and the government in 1606 prohibited "all cultivation of tobacco in the Spanish Caribbean possession for at least 10 years.” The local administrative government in Santo Domingo protested immediately against the prohibition, knowing that many people depended on the cultivation of tobacco for their ‘sustento y conservacion’ (Baud). The final argument against the prohibition was the large consumption of tobacco by African slaves, who would "become restless when tobacco supply dwindled." The same argument was used by the governor of Caracas who complained that the "Pearl-fishing slaves in Margarita hardly worked when there was no tobacco" (Baud).

Tabako has always had its roots in indigenous culture and its uses have transformed many times through its cultivation and exploitation. No matter what perception we may have of this plant, we have come to know its value has very few limits. For centuries, it has affected the lives of those who had colonial ties to their oppression. Used as an engine to drive the economies of different colonizing powers, the resilience of this plant and the agrarian people who have spiritual connections to it still exist today. It is with this knowledge that we can begin to honor those who lived and fought for their livelihood. Those who were persistent and survived while maintaining the integrity of their culture and beliefs.