The Ozark region has long been recognized as a geologically, physiographically, ecologically, and culturally distinct area of North America. In conjunction with the Ouachita region to the south, the Ozarks comprise the only significant highland in midcontinental North America, and the only notable topographic relief between the Appalachians and the Rocky mountains.

This region is characterized by a diversity of terrestrial, aquatic, and karst habitats, ranging from extensive glades and tallgrass prairies to both coniferous and deciduous woodlands and cypress swamps, as well as fens, sinkholes, sloughs, and a suite of clear-flowing streams and rivers fed by an abundance of springs of all magnitudes, including some of the largest freshwater springs in North America.

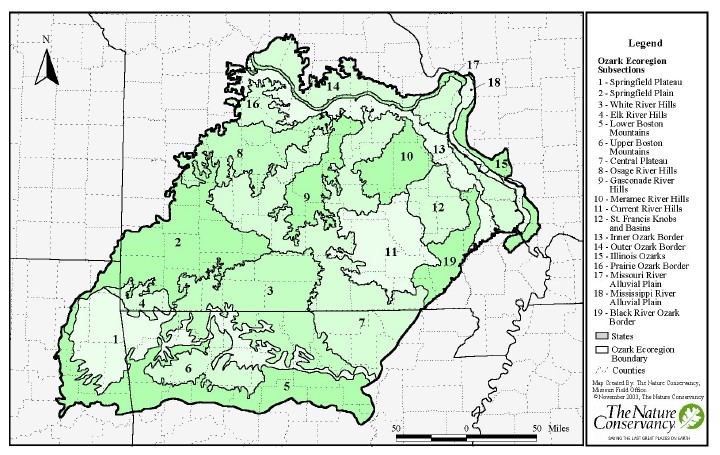

Encompassing 13.7 million hectares (34.3 million acres), the Ozarks include portions of five states, with the majority of the region occurring within Missouri (67%) and Arkansas (24%) and smaller portions in Oklahoma (17%), Illinois (2%) and Kansas (0.1%). The Ozarks span a maximum of 270 miles (450 km) of north/south extent, and a maximum east/west extent of 340 miles (540 km). As shown in Figure 1, six other ecoregions, ranging in character from tallgrass prairie landscapes to humid forested wetland systems, border the Ozarks ecoregion.

High levels of topographic, geologic, edaphic and hydrologic diversity exist throughout the Ozarks, resulting in a wide range of habitat types. This is a region of rugged uplands with copious exposed rocks and variable soil depths. The landscape in various terrestrial subsections of the Ozarks ranges from extensive areas of karst terrain on irregular plains, to highly dissected regions with steep hills and deeply entrenched valleys, as well as limited areas of ancient low mountains with elevations up to 925 meters (3000 feet). There are also smaller, linear areas of alluvial terrain and major riparian features.

Bedrock geology of the Ozarks includes exposures of Precambrian igneous rocks in the eastern part of the Missouri Ozarks surrounded by alternating zones of Paleozoic sandstone and carbonate sedimentary rocks. Structurally, the Ozarks consist of a dome that has been slowly uplifted and eroded, resulting in a distinct landscape pattern. The oldest igneous rocks are exposed at the center of the uplift in southeast Missouri and surrounded by regions of Cambrian- and Ordovician-aged shallow water carbonates and beach sandstone strata. Further from the center are areas of younger Mississippian sedimentary rocks, including limestones and limited areas of riparian-derived freshwater sandstones (Nigh and Schroeder 2002).

Dominant soils consist of Alfisols and Ultisols. The Alfisols, predominant in the less dissected terrestrial subsections, are thin loams with a clay component in the subsurface, and are generally thought to have formed under timber and some prairie vegetation types. Ultisols, predominant in the more rugged and dissected terrestrial subsections of the Ozarks, can in many ways be considered a more leached, weathered version of alfisols, with a much lower component of basic cations. Average precipitation in the Ozarks ranges from 39-52 inches (99-132 cm), with mean annual temperatures ranging from 54-63 F (12-17 C). The average frost free growing season ranges from 180-208 days.

A major contributing factor to the region’s extreme biological diversity is that parts of the Ozarks have been continuously available for plant and animal life since the late Paleozoic some 230 million years ago, constituting perhaps the oldest continuously exposed land mass in North America, and one of the oldest on earth. Plants have presumably inhabited these rugged uplands since the origin of the modern angiosperms some 100 million years ago. Because of their central location within the continent, the Ozarks have on multiple occasions served as a refugium for organisms buffeted by climatic shifts associated with glacial and geologic events. The high levels of microhabitat diversity, influx of biota from divergent regions, and extreme antiquity of the landscape have combined to both sustain relictual populations and allow the development of new species, making the Ozarks a center of endemism in North America (i.e., Zollner et al. 2005).

None of the four major continental glaciation events of the past two million years extended into the Ozarks. At the maximal extent of Wisconsin glaciation some 15,000 years ago, the climatic effects of a massive ice lobe extending into what is now central Iowa resulted in a boreal climate through much of midcontinental North America. At that time, the vegetation of the Ozarks was a combination of spruce-fir forests and jack pine parklands (Delcourt et al. 1986).

Coincident with or preceding the glacial retreat, there has been a more or less continuous inhabitancy of the region by human cultures. These people had to secure all the necessities of survival from the local environment on a year round basis without significant trade or resource input from areas outside the Ozarks. The fact that such cultures not merely survived, but developed art, mythology, ceremony, religion, and other accoutrements of highly developed societies, testifies to their superb abilities to manage and interact with the Ozark environment.

One of the most pervasive and effective tools available to early human populations in the region was wildland fire. An irrefutable body of evidence exists that the biological landscape of the Ozarks reflects the effects of millennia of frequent, low intensity, dormant season fires set by humans (e.g., Ladd 1991, Guyette & Cutter 1991). At the initiation of European settlement of the region, predominate Native Americans in the Ozarks were the Osage. Parts of the eastern and southeastern Ozarks were home to the Quapaw.

Thus, the pre-Eurosettlement vegetation in the Ozarks had been influenced since the end of the glacial period by an ongoing aboriginal fire regime. This vegetation consisted of a mosaic of matrix communities dominated by open woodland types, with various combinations of oaks and shortleaf pine as the principle overstory dominants in the uplands. Although Ozark woodlands differ significantly from the extensive deciduous woodlands extending eastward to the Atlantic coast, the Ozarks represent the westernmost extension of this eastern deciduous woodland formation that dominated much of eastern North America prior to European settlement. Extensive areas of tallgrass prairie occurred in the Ozarks, especially in the western terrestrial subsections (Schroeder 1981). Embedded within these matrix vegetation types was a diverse assemblage of small and large patch natural communities, including various types of fens, forests, wetlands, fluvial features and both carbonate and siliceous glades. The Ozarks ecoregion contains the largest extent of glade communities in North America (Nelson and Ladd 1980), and the extensive landscape of dolomite glades in the White River Hills section of the Ozarks in southwestern Missouri is globally unique.

As a direct result of all of these factors, the Ozarks support a diversity of natural communities and associated biota unlike anywhere else on earth. Many plants and animals in the Ozarks are relict populations of organisms whose modern ranges are otherwise remote from the region. A combination of habitat diversity, landscape position, and glacial history has resulted in a large number of species with diverse biogeographic affinities attaining the limits of their ranges within the Ozarks. For example, an evaluation of the Lower Ozark region of southeastern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas (predominately in the Central Plateau and Current River Hills terrestrial subsections) revealed that an astounding 17% of the area’s vascular flora attained their global range limits in the Ozarks (TNC 1993).

The Ozarks also constitute a center of endemism for temperate biota in divergent organismal groups including vascular plants, lichens, fish, mollusks, and crayfish. Although not attaining levels of endemism associated with certain tropical systems, at least 200 taxa of plants and animals are known to be endemic to the Ozarks and/or Ouachitas (Allen 1990), despite a lack of disciplined biological inventory through most of the region, especially among more cryptic organismal groups. For these reasons, the area has long been recognized by conservation practitioners for its biodiversity and conservation significance.

The region has been significantly impacted by anthropogenic activities associated with modern society. This trend is accelerating, as intensive residential and recreational development, woodland clearing for pasture, and confined animal operations become ever more prevalent in the landscape. The Ozarks currently hosts a human population of more than three million people. Despite this, large areas of the Ozarks remain in native vegetation cover. Timber, tourism, and agriculture are major economic factors in the region, with a rapidly increasing influx of retirees in recent years. Overall population trends are upward in the region. Average education and income levels throughout the Ozarks are generally lower than national averages, and 29 Ozark counties are classified as “persistent poverty” counties by the USDA. Critical threats to biodiversity across the region include altered fire regimes, altered hydrological regimes, habitat conversion and associated exotic species invasion, habitat fragmentation, and non-point-source pollution.

With it diverse geology, topography, and microhabitat spectrum, the Ozarks support a surprisingly rich diversity of lichens. Lichens are a prominent component of every intact landscape, including the prairie regions of the western Ozarks. Lichen diversity and abundance are impacted in the urban, suburban, and densely agricultural districts of the Ozarks. However, even in the most urban portions of St. Louis, the largest city in the Ozarks, one can consistently observe disturbance-tolerant lichens such as Arthonia caesia, Caloplaca feracissima, Candelaria concolor, Endocarpon pallidulum and Physcia millegrana.

The prevailing matrix natural community through most of the Ozarks is some phase of a variable deciduous wooded upland complex on leached acidic soils with abundant chert residuum. These woodlands are dominated by various species of oaks, such as Quercus alba, Q. coccinea, Q. marilandica, Q. stellata, and Q. velutina. Associated with these oaks are a consistent subcomponent of hickories such as Carya glabra, C. texana and C. tomentose, as well as a diversity of other trees, notably Cornus florida and Nyssa sylvatica. The corticolous lichen biota of these woodlands is dominated by a mixture of foliose and crustose taxa, with Pertusaria, Phaeophyscia and Physcia being among the most diverse and abundant genera. Canopy lichens in intact wooded uplands can be extremely diverse, with a number of fruticose taxa such as Ramalina culbersoniorum, Teloschistes chrysophthalmus, and Usnea spp., as well as Buellia stillingiana, Flavoparmelia caperata, Hypotrachyna livida, and Myelochroa galbina Pioneer lichens on young canopy branches include Amandinea polyspora, Arthonia quintaria, Lecanora strobilina and Physcia stellaris. The leached, acidic soils in the woodlands support a diverse suite of Cladonia species, while the chert cobbles and boulders provide habitat for a diversity of saxicolous lichens, including Buellia maculata, Fellhanera silicis, Flavoparmelia baltimorensis, Myelochroa aurulenta and M. obsessa.

In the southern half of the Ozarks are extensive regions that were dominated or codominated by shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata). These extensive pineries were the basis for an intensive logging boom at the turn of the last century, and for a brief interval in the early 1900’s the largest sawmill in the world was located in the southeastern Missouri town of Grandin. Although the extensive pineries (and much of their sensitive biota, such as red-cockaded woodpeckers) are gone, considerable pine remains in this part of the Ozarks, and pines in remnant woodlands host a unique association of lichens, including Canoparmelia caroliniana, C. texana, Chaenothecopsis nana, Cladonia ravenelii, Hypotrachyna pustulifera, Lecanora minutella , Tuckermanella fendleri and Tuckermanopsis ciliaris. Older cones of these pines are invariably colonized by Amandinea punctata and Lecanora strobilina.

Limited areas of wet to mesic woodland, and even actual forest habitat, occur along streams and in deeper ravines. Prominent canopy trees in these habitats include Carya cordiformis, Fraxinus americana, Quercus rubra, Q. shumardii and Tilia americana, with understory species such as Carpinus caroliniana. Larger rivers, with significant silt deposition associated with flood events, have floodplains and margins with Acer saccharinum, Betula nigra, Fraxinus pennsylvanica subintegerrima, Platanus occidentalis, Populus deltoides and Salix nigra. Lichen development in these habitats ranges from depauperate in areas with excessive flooding to among the richest in the Ozarks in stable, intact sites with perennially high humidity levels. Some of the regions rarest lichens, such as Graphis sophisticascens, are associated with these habitats.

Glades are predominately open natural communities with bedrock at or near the surface. Glades are usually located on west and south aspects, because of the increased solar desiccation associated with these aspects, and its consequent inhibition of woodland development. Two general classes of glades occur in the Ozarks: carbonate glade, developed on dolomite and limestone; and siliceous glades, developed on sandstone, igneous rocks, and chert. The world’s only chert glades occur on the massive chert exposures near Joplin in southwestern Missouri. Siliceous and carbonate glades support very different assemblages of both vascular plants and cryptogams. Differences among the lichen biota in glades of specific rock types within major glade classes are minor but evident.

The most prominent feature of siliceous glades is the abundance of various species of Xanthoparmelia, which provide the main color feature on many siliceous glades. Intact examples of siliceous glades support a high diversity of lichens, including several species that are rare or unusual in the Ozarks, such as Psora icterica and Pycnothelia papillaria. The saxicolous lichen component of carbonate glades is less prominent, consisting mostly of relatively inconspicuous crustose taxa. Nonetheless, it is at least as diverse, and perhaps more significant, with a number of new species whose global distribution is uncertain, some of which may prove to be Ozark endemics.

LITERATURE CITED

Allen, R.T. 1990. Insect endemism in the Interior Highlands of North America. Florida Entomologist 73: 539-569.

Delcourt, H.R. et al. 1996. Vegetational history of the cedar glades regions of Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri during the past 30,000 years. A.S.B. Bulletin 33: 128-137.

Guyette, R.P. and B.E. Cutter. 1991. Tree ring analysis of fire history in a post oak savanna in the Missouri Ozarks. Natural Areas Journal 11: 93-99.

Ladd, D. 1991. Reexamination of the role of fire in Missouri oak woodlands. Charleston, IL: Proceedings of the Oak Woods Management Workshop: 67-80.

Nelson, P. and D. Ladd. 1980. Preliminary report on the identification, distribution and classification of Missouri glades. Proceedings of the 7th North American Prairie Conference: 59-70.

Nigh, T.A. and W.A. Schroeder. 2002. Atlas of Missouri ecoregions. Jefferson City, MO: Missouri Department of Conservation.

Schroeder, W.A. 1981. Presettlement Prairie of Missouri. Jefferson City, MO: Missouri Department of Conservation Natural History Series No. 2, 37 pp.

The Nature Conservancy. 1993. Lower Ozark project ecological overview. St. Louis, MO. 42 pp.

Zollner, D., M.H. and B.R. MacRoberts, and D. Ladd. 2005. Endemic vascular plants of the Interior Highlands, U.S.A. Sida 21: 1781-1791.